This article was originally published in the Harvard Gazette.

Today’s racial climate has been compared to some of the darker periods of the American past. From the murder of George Floyd to the Kyle Rittenhouse and Ahmaud Arbery cases, violence, extremism, and unrest have put the nation on edge.

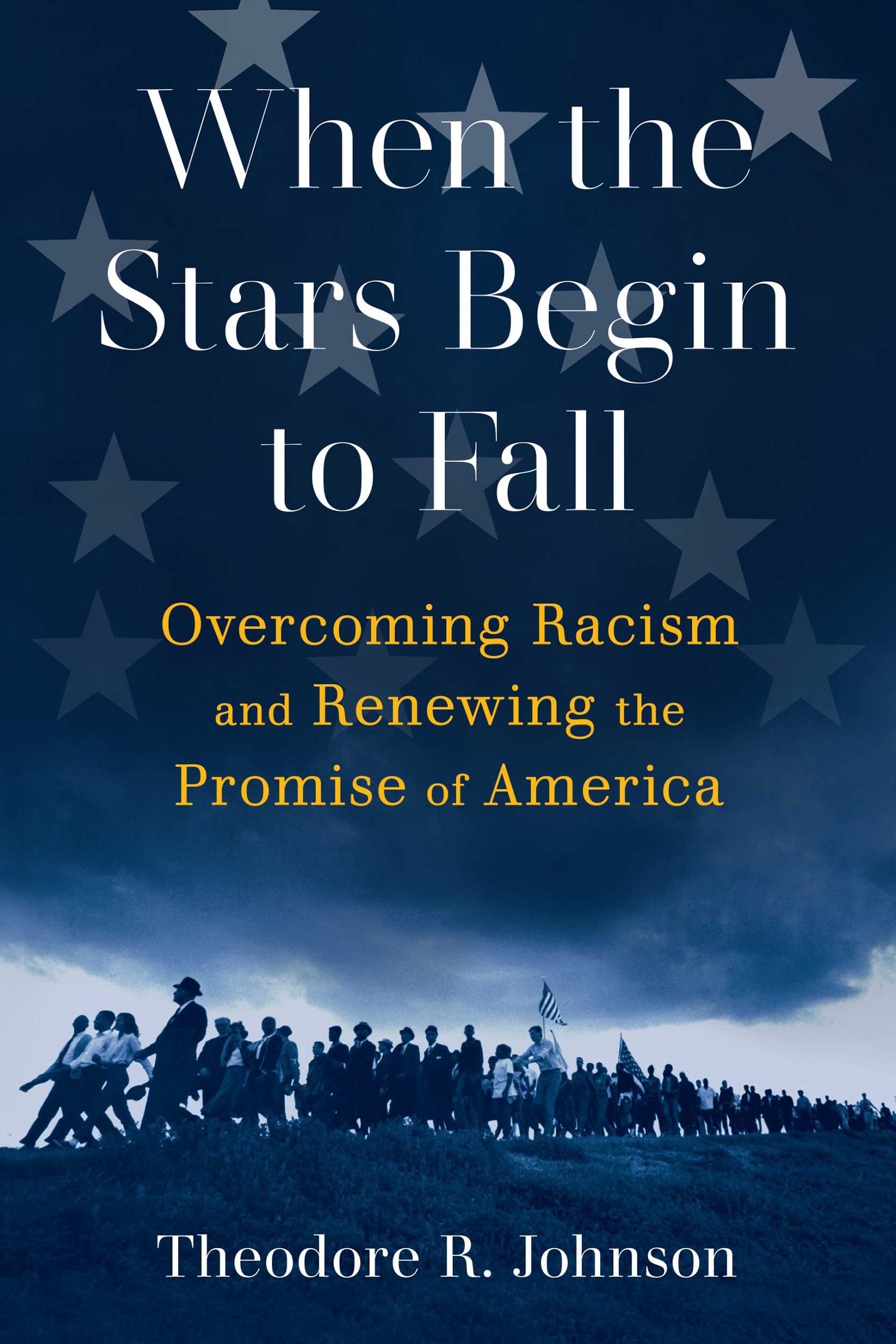

In his new book, “When the Stars Begin to Fall: Overcoming Racism and Renewing the Promise of America,” Theodore R. Johnson, ALM ’11, delves into the United States’ racist history in search of solutions to the “existential threat” that continues to shadow the land. Johnson, a former Navy commander, spoke to the Gazette in relation to Harvard Extension Alumni Association’s Author Spotlight series, where he was a December 2021 guest. The interview was edited for clarity and length.

Q&A

Theodore R. Johnson

GAZETTE: How did you come to the idea for this book?

JOHNSON: In 2012, I went and spent four years in the Pentagon, working on things related to cybersecurity, and then spent a year and a half as the speechwriter to the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. What I also did, in my Pentagon time, was get a doctorate in law and policy from Northeastern, because I recognized that I wanted to do more than just think about what other nations were trying to do to us in cyberspace, and I wanted to think more deeply about the state of America, particularly as it relates to the question of race. And my study of law and policy, with a particular focus on African American voting behavior, was what I spent my doctoral time doing. In 2018, I landed in my current position — senior fellow at the Brennan Center for Justice. And there, I’ve spent most of my time writing the book that my dissertation sort of started, and thinking lots about Black American voting behavior, particularly as it pertains to the 2018 midterms and the most recent presidential election.

GAZETTE: You use the term “trickle-down citizenship” when you talk about America. How do you see trickle-down citizenship playing out right now?

JOHNSON: Trickle-down citizenship is a political strategy I described in the book that Black Americans, and some other groups as well, have used to gain more access to the rights and privileges of citizenship in the United States. If you are a marginalized group, a group that’s been excluded from democracy and is trying to convince the nation that it should be included, if the demand to be included is only made on moral grounds, it is usually insufficient to result in their inclusion. What trickle-down citizenship says is that nation-states are governed by their interests, not by some absolute sense of goodness or morality. If you want to compel a nation-state to act, you must marry your moral demand with a national interest.

During the Civil Rights Movement, not only did Black Americans make a moral claim to be treated as fully American, but they married their moral claim to the nation’s interest in winning the Cold War. And it’s no coincidence that from 1948 to 1968, when we see two decades of tremendous progress on civil rights in this country, also is the time when we’re in the thick of the Cold War against the Soviet Union. It’s not a coincidence that the abolishment of slavery comes at a time when the national interest was about reunifying. So, to the extent we can marry moral claims with the national interest, then the rights of citizenship begin to trickle down to those excluded and marginalized groups and bring them into the fold of democracy.

GAZETTE: We can see those examples you’ve cited in the events of the summer of 2020 and the Black Lives Matter movement, when protests started to gain a lot of interest and traction. But what many have noted is that the events of that summer led to an almost a complete reversal of sentiment and pushback in some states by those in power to take away some rights, particularly voting rights. Why do you think such a strong pushback occurred?

JOHNSON: Backlash is almost always paired with progress, especially progress that happens over a relatively short period of time. It was to be expected that after the summer of 2020, when we have racial justice protests happening in every state in the country for weeks on end, following the murder of George Floyd, the killing of Ahmaud Arbery, the killing of Breonna Taylor, and a global pandemic. Not to mention at the time the economy, the bottom falling out and a lot of people losing their jobs and becoming economically insecure. All these things are happening just as George Floyd is murdered. And we see a summer of people sort of reclaiming their civic engagement, their desire to be around one another, but also expressing their dissatisfaction with how government has responded to these crises of democracy and justice.

Now the question becomes, will we reject that backlash and try to mitigate it? Or will we accept that some of this backlash is a sort of course correction from racial progress reaching too far?

The last thing I’ll say on this is that it doesn’t require actions in order for a backlash to occur. When President Obama was elected, he came into office singing a song of unity, wanting to bring people together. He did nothing. When he came into office, that was explicitly racial. On the surface. Everything he did was color-blind. Obamacare was color-blind, really helping the country recover from the housing boom, the housing bust was color-blind. But his very presence, for a Black man in the White House, a Black family in the White House, elicited a backlash because it changes the story of America, this office that had always been held by white men is suddenly held by a Black man with a Black family, a Black man who is the son of a Kenyan immigrant with a Muslim name. And that changed too much of the American mythology for some, and I think the Tea Party movement that grew out of Obama’s election and materialized just a year and a half later. And I think the election of Donald Trump was the backlash to the two-term presidency of a Black president.

GAZETTE: What path does America need to take to reclaim the promise that this nation is for everyone?

JOHNSON: In the book I say that there is a path, but we can’t say yet it how we can get on the path and stay there. Often you might hear people say, “Well, war has brought us together.” But the book questions whether that is the case. After World War II, the federal government, on orders of President Roosevelt, who some consider one of the greatest presidents in the country’s history, gave the order to round up Japanese Americans and put them in camps, on suspicion of being spies, or just in case there were. So, in this time of incredible unity, we rounded up people based on their ethnicity and put them in camps. After 9/11, George Bush had to say, we are not at war with Islam, and he had to go to mosque to get people to stop hating and committing violent crimes against Muslims. I don’t think war is the answer. If someone had asked, “What about a natural catastrophe not attached to war?” I would say that could potentially do it. And then COVID happens. We weaponize the virus, mask wearing, and who is or isn’t taking the vaccine.

GAZETTE: So what’s next for the United States?

JOHNSON: In the book I try to give people something to grab onto. This isn’t an exact blueprint but some suggestions I think could get us on the path forward. We must reform our institutions of democracy, which means we must get rid of gerrymandering and protect and expand voting rights, we have to get like big money out of politics so that those with lots of money and resources don’t outweigh the wishes of just regular Americans. Some institutional reforms must happen. We also need more civic education, not just how many branches of government are there, but we must train people to be active citizens in a democracy, and not just in elementary and high school. We need to have a way of keeping citizens engaged and informed. Another is this idea of deliberative democracy, which is when people come together in town hall kind of settings, but the decisions they come up with are binding on local government. That sort of brings people together to debate ideas, instead of arguing about identities.

I think if there was one silver bullet, and there isn’t, but if there was one thing closest to it, that I think would help us mitigate the effects of structural racism on America, it would be creating conditions that force more of us to interact with people who are unlike us, and we don’t have to wait for programs to do that. We can do that ourselves.