The next major bust, 18 years after the 1990 downturn, will be around 2008, if there is no major interruption such as a global war.

Fred E. Foldvary (1997)

The destructive wave that swept across the US economy in 2008 seemed to catch the world completely by surprise. The phrase so often used to describe it, a “financial tsunami,” reinforces the popular belief that the disaster arose suddenly.

In reality the build up to the Great Recession could be clearly tracked and its timing predicted with a stunning degree of accuracy long before the phrase “collateralized debt obligation” entered the popular lexicon.

The real cause of the crisis is far older, far more interesting, and far more profitable to understand for those interested in what lies ahead.

As early as 1876, Henry George observed the curious cycle through which real estate markets inexorably move. His findings can be summarized (with the help of Glenn R. Mueller’s refinements) as follows.

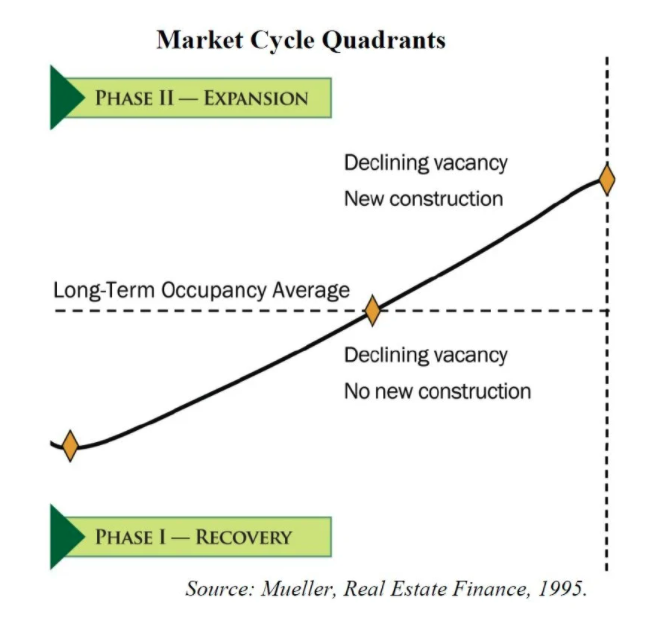

Phase I: Recovery

We know the characteristics of a recession: high unemployment; decreased consumption; and decreased company investment in buildings, factories, and machines. The price of land, essential for economic activity, is at its lowest point in the cycle.

As population increases so does the demand for goods and services. This expansion is typically hastened by government intervention in the form of lowered interest rates (the key ingredient for investment).

With increasing demand and lower investment costs, companies expand their businesses. They hire more people, build new factories, and buy more machines. This expansion adds to the demand for land (buildings) on which the economic activity can take place.

Vacancy across all real estate asset classes (office, retail, residential, etc.) decreases as companies use previously empty buildings and individuals move into previously vacant homes.

Phase II: Expansion

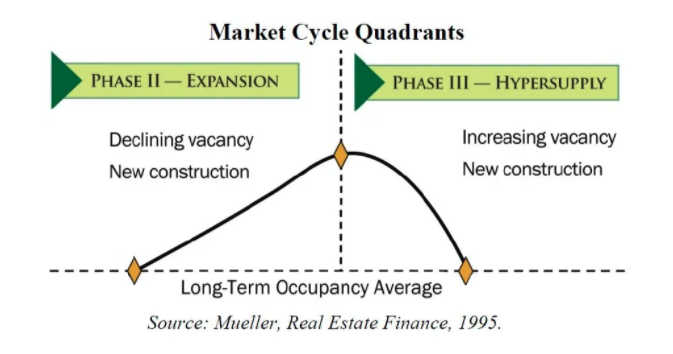

The transition from recovery to expansion occurs when companies and individuals have bought up or rented most of the available buildings. Occupancy begins to exceed the long-term average. As unoccupied buildings become scarce, landowners raise rents.

Since most real estate expenses are fixed, increased revenues translate almost dollar-for-dollar into increased profits. Increased profits attract new development of vacant land or redevelopment of existing properties.

Basic economics tells us that new supply will satisfy demand and eliminate the upward pressure on rents and land prices accordingly. But here’s the twist: it takes a long time to add new inventory to the real estate market once it’s needed.

Market studies must be undertaken. Land sales must be negotiated. Zoning and permitting must be obtained. Financing for the project must be found (no easy feat coming out of a recession). Only then does new construction begin. And the construction itself takes a long time (two to five years for the average development).

By the time meaningful amounts of inventory start to come online, the overall economic expansion has been under way—without the benefit of new supply—for five to seven years. During all of that time, occupancy rates and rents have been increasing.

In fact, the cycle reaches a point at which rents are not simply going up—they are going up faster and faster (rent growth is accelerating). Investors build this trend into their forecasts. And we reach that critical point in the real estate cycle where, as William Newman documented as far back as 1935, the price of land begins to reflect not the existing market conditions but rather the anticipated rent growth to come.

Investors, believing the price is justified by the future growth, overpay for the land relative to the current market, and start building for a future market. The boom is officially on.

Phase III: Hyper Supply

As long as the current occupancy rate exceeds the long-term average, there will be upward pressure on rents. As long as there is upward pressure on rents, new construction is financially feasible. This is the case for both the expansion and hyper-supply phases.

The First Indicator of Trouble

The delineation point between expansion and market hyper supply is marked by the first indicator of trouble in the real estate cycle: an increase in unsold inventory/vacancy.

This occurs as new completions from the mid-expansion phase begin to quench the market’s thirst for product. With occupancy rates above the long-term average, rents are still rising but the rate at which they are rising now changes: rent growth is no longer accelerating, but rather decelerating.

This is a precarious time in the real estate cycle. And what happens next will determine how severe the upcoming recession will be.

Wise developers, noting the change in direction of rent growth and factoring in the likely consequence of units currently under construction being completed, should choose to stop building. If you find such a developer, please let me know.

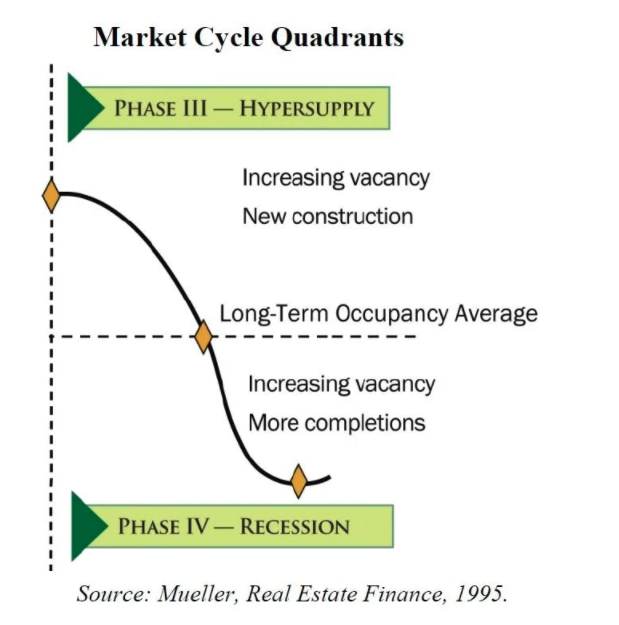

Phase IV: Recession

The Second Indicator of Trouble

The transition from hyper supply to recession is marked by the second indicator of trouble in the cycle: occupancy falls below the long-term average.

New construction stops, but projects started in the hyper-supply phase continue to be delivered. The addition of surplus inventory leads to lower occupancy and lower rents, which significantly reduces revenue for landowners.

The Third Indicator of Trouble

Finally, investors must watch for the third indicator of trouble: an increase in interest rates.

The increases in prices throughout the broader economy that accompanied the expansion and hyper-supply phase will, sooner or later, force the Federal Reserve to fight inflation by increasing interest rates.

The good news is that this halts any developers still forging ahead in hyper-supply mode because the increase in borrowing costs makes new developments financially unfeasible.

The bad news is that it’s too late for the projects started in the midst of the boom. The music stopped, but there are still people rushing toward the dance floor.

The combination of lower occupancy, lower rent received on those occupied units, and increased interest expenses (a large fixed cost) quickly erodes landowners’ profits.

There are broader issues from the shutdown of the economy’s largest growth engine (new construction), but that is for another discussion. Suffice it to say, the downturn in the Real Estate market has a huge impact on the economy as a whole which, in turn, pushes the Real Estate market down further.

Vacancy stalks landowners and, as revenues fall below landowners’ fixed costs, foreclosures follow. The real estate cycle comes full circle and, as Foldvary (2007) notes, “shrewd investors pick up real estate bargains.”

The Duration and Frequency of the Real Estate Cycle

Perhaps the most stunning aspect of the real estate cycle is not its inevitability but rather its regularity. Economist Homer Hoyt, through a detailed study of the Chicago and broader US real estate markets, found that the real estate cycle has run its course according to a steady 18-year rhythm since 1800.

With just two exceptions (World War II and the mid-cycle peak created by the Federal Reserve’s doubling of interest rates in 1979), the cycle has maintained its remarkable regularity even in the decades after Hoyt’s observation.

Where Are We Now?

It’s important to remember that the Great Recession was not caused by an unexpected event. To those who study the real estate cycle, the crash happened precisely on schedule. It was painful, but it inaugurated the next iteration of the real estate cycle.

Today, most real estate markets are well into the expansion phase. Many, as indicated by skylines filled with cranes and slowing rent growth, have already entered the hyper supply phase.

Those who study the financial crisis of 2008 will (we hope) always be weary of the next major crash. If George, Harrison, and Foldvary are right, however, that won’t happen until after the next peak around 2024.

Between now and then, aside from the occasional slow down and inevitable market hiccups, the real estate industry is likely to enjoy a long period of expansion.