Addressing the Orphan Crisis in Ethiopia

Fifteen years ago, Dinsry Berhanu stepped into an Ethiopian orphanage for the first time. She was stunned by what she saw.

“It was a small residential home with a few bedrooms,” Berhanu says. “There were at least 40 kids living there. When I walked into the compound, the kids were all over me. I realized how starved these kids were for one-on-one interaction. No child deserves to live in that type of environment.”

Berhanu was in her early twenties during this visit to her home country. A friend adopted three Ethiopian siblings and couldn’t make the trip, so Berhanu traveled from the United States to meet the children and bring them to their new home.

That day was a turning point for Berhanu. Since then she has devoted endless energy to advocate for abandoned Ethiopian children.

Too Many Orphans, Too Few Adoptions

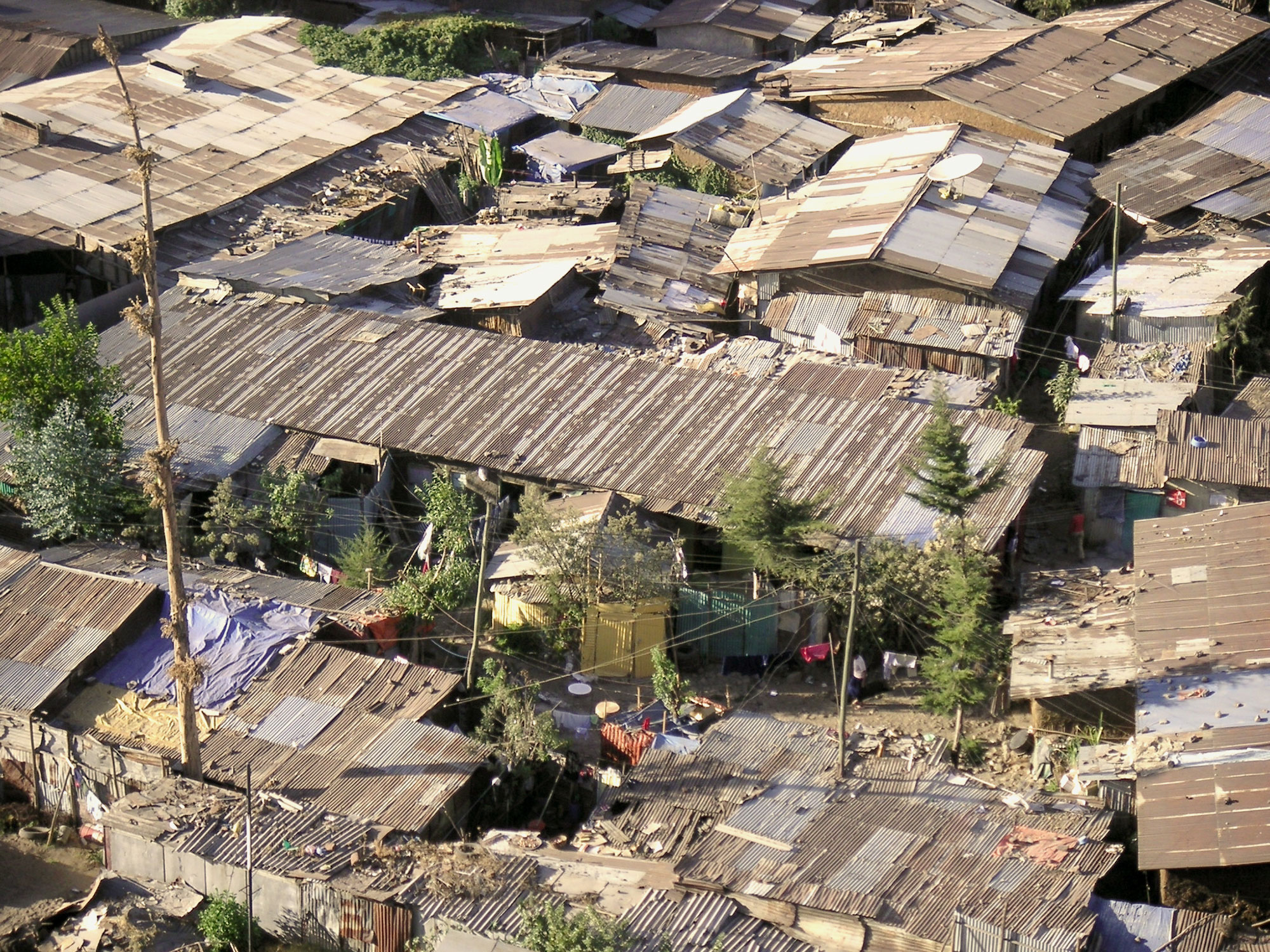

The orphan crisis in Ethiopia looms large, reflecting many of the other countries in sub-Saharan Africa. According to Berhanu, about four million Ethiopian children have lost one or both of their parents. A recent UNICEF report states that there are 4.5 million orphans in the country, out of a total population of about 90 million.

Over the past 15 to 20 years, a few major causes have served to blame, particularly the ravaging effects of HIV and AIDS, and crippling poverty that forces parents to abandon children they cannot afford to raise.

In some parts of Ethiopia, adoption is a more common practice. But in many areas, a strong mindset against adoption prevails — to the degree that many locals even discourage other community members from adopting, says Berhanu.

“There is a saying in our language: ‘One would rather raise a puppy than someone else’s child,’” says Berhanu. “People are afraid another child will share their biological children’s inheritance, or grow and reconnect with the child’s biological family.”

Building the Knowledge to Support Emotional Development

One of the ways Berhanu hopes to mitigate the orphan crisis is to work directly with the children. She began volunteering at various orphanages and mentoring the vulnerable kids in her community.

Berhanu started noticing that many of the kids lacked some basic skills, such as the ability to regulate their emotions and make eye contact. This prompted her to study attachment theory and emotional development. And in 2010 she discovered that Harvard Extension School — where she had taken a few nonprofit management courses while living in Massachusetts — was offering an online psychology class on early childhood development.

Berhanu fell in love with the class, and later decided to enroll in a master’s degree program in psychology at the Extension School. Studying early childhood development provided a theory-based education that supplemented her more practical education with the kids in her community.

Through a carefully scheduled curriculum of online and on-campus study, Berhanu was able to earn her degree from nearly 7,000 miles away, allowing her to have limited interruptions in her on-site work at the orphanages.

“I’m not in the position to abandon everything I have started here to go to the US for two or three years to do my master’s,” Berhanu says. “The hybrid program has really worked for me.”

Reverse the Mindset and Reshape the Policies

In addition to working directly with children and studying early emotional development, Berhanu has recently started tackling the negative mindset toward adoption. Two years ago she produced an educational documentary film about domestic adoption in Ethiopia. She hopes the film can help reverse these strong sentiments regarding adoption practices.

“Six Ethiopian families who have legally adopted Ethiopian kids shared their experiences in the documentary — their challenges, their joys,” Berhanu says. “In order to promote family adoption as an option, we need to change this [antiadoption] mindset. We have been using this film here in Ethiopia and in the US among the Ethiopian community there to create the platform for discussion.”

My efforts seem small. … And yet, it is rewarding. If I can change the life of one child, that’s good enough for me.

Berhanu’s efforts don’t stop there. She organizes summits for local stakeholders to promote family-based care for children living in institutions. She trains orphanage caregivers to incorporate arts and crafts and sports into their daily routine. She is also trying to create a network among child-based organizations so they can more readily communicate and share responsibilities. Some day she hopes to adopt a child of her own, when the time is right.

A Mission-Driven Career Path

Naturally, with such dedication comes difficulty. The work is heart-wrenching and the problem pervasive. And making a living doing such selfless work is not easy. All her work to this point has been on a volunteer basis.

As Berhanu attempts to build a sustainable career, she hopes to transition from the grassroots level to a more policy-based focus. She conducted a fair amount of research in preparation for the documentary film, and hopes to expand this research — perhaps as part of her thesis — so she can help address the policy gaps surrounding child protection and welfare.

“My efforts seem small. Although the mindset is changing, and Ethiopians are adopting, the pace is not quick enough for me, so it is frustrating,” says Berhanu. “And yet, it is rewarding. If I can change the life of one child, that’s good enough for me.”

— Story by Lauren McLaughlin